Raymond rose from his chair opposite me, came around, stood behind me, and proceeded to put his hand down inside the front of my shirt. “Oooh, that’s a big pec,” he said, as he felt my pectoral muscle. Don’t you have to buy me dinner first, I thought but didn’t say. He went on, adding “I can’t put the unit under that pec, it simply won’t charge. I’ll have to put it just under the collarbone.”

The neurosurgeon was talking about the combined stimulator and battery unit that was to be implanted in my chest, a part of the deep brain stimulation (DBS) system proposed to be put into my body.

Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in the brain is highly effective in alleviating debilitating symptoms in people with Parkinson’s disease. I had opted for DBS as an advanced therapy for my Parkinson’s disease and was in Sydney to meet the team and go through some preliminary testing, known as the workup week, to ensure I was a suitable candidate.

I met with Paul, the neurologist and team leader, on multiple occasions, and also had two lengthy sessions with Linton, the team’s neuropsychiatrist. And of course, a two-hour discussion with the neurosurgeon.

Before moving away from behind me, Raymond placed his hands on my not-insubstantial cranium, commenting, “Hmm, it’s a big head … ” almost to himself. Yes, it’s a melon, that’s for sure. The last Akubra I bought had my head circumference measured at 63 centimetres, and I wear a size 7 7/8 baseball cap. So, what’s wrong with a big head, I asked. He bluntly stated “ … it will only just fit into the stereotactic frame that will be bolted to your head to guide the placement of the leads.”

When I related the ‘big pec’ story to my exercise physiologist, he said, “Of course, we’ve been working hard on making you strong!”

Why DBS?

So why did I choose DBS as an advanced therapy? Well, thanks for asking!

Need

I was quickly reaching the point of needing advanced therapy. My Parkinson’s had progressed considerably in 2022, to the point where I was on the maximum dose of all of the medications. I was getting about one good hour out of every three where I was on, and I tried to do what I could in that hour. The rest of the time was either running off or ramping back up to an on state. I could make it through a day on 150 mg of levodopa (the main dopamine replacement drug) every three hours, but I wouldn’t be able to do much. Think about a daily energy usage budget in dollar terms, let’s say $100 for the day. I can’t keep the money from yesterday and I can’t borrow from tomorrow. So having a shower and getting dressed in the morning costs me $20. A training session with my exercise physiologist is $50. Cooking a meal by myself, $25. The day’s budget doesn’t last long, and if I’m out of money by 4:00 p.m., that’s it, I’m done for the day. If I persisted and spent money I didn’t have, I ended up hungover the next day or even two, without the excessive drinking!

A 150 mg tablet would not get me through an hour of training, as the extended release medication would not release enough dopamine to keep up with demand. I could get through a gym session on a 200 mg tab, but would need a brief rest afterwards before I left the premises. However, if I took a 200 mg tab and didn’t do any physical activity, I would have too much dopamine in my body which gave me the horrible over-medicated wriggles of dyskinesia. On weekends during baseball season, I would bunch up my 200 mg meds to two hourly doses just to give me enough capacity to get through a few hours of coaching a game.

Timing

Considering the circumstances I was in, the time was right for me to be considering advanced therapy.

The image below, courtesy of the Sydney DBS website, is a simple representation of a typical timeline for the progression of Parkinson’s. The diagram shows that as time passes the state of being on, where medications are working effectively, gradually narrows.

When a person is diagnosed with Parkinson’s, the part of the brain that makes dopamine, called the Substantia nigra, is 75 percent gone. That person would lose an additional one percent every year, whereas a non-afflicted person would lose one percent every ten years as part of the normal ageing process. There is a widely held belief that the medications have less efficacy over time, but this is untrue. It is simply a fact of the progressive nature of the disease. When one is constantly losing dopamine-producing cells at a comparatively high rate, medications struggle to keep up. As one jams that medication in, the high doses can lead to dyskinesia where too much dopamine causes uncontrolled movements.

Another consideration regarding timing is that I am young, strong, healthy, and active. Paul stated that he can only work confidently with patients that are in a good place, rather than people that turn to DBS as a last resort. He said, “If you turn up in a wheelchair, I won’t be able to get you out of the wheelchair … “

The last consideration is that I need to have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s for at least five years. The team will not operate on a newly diagnosed person as there may be a chance that the symptoms may indicate Parkinson’s but might actually be representative of Lewy Body Dementia or Multiple System Atrophy, both of which cannot be treated with DBS. A period of about five years is enough for these conditions to raise their ugly heads. It was exactly eight years between my diagnosis and my DBS surgery – I don’t know whether this is serendipitous, uncanny, or just a coincidence.

Other options

There are two other options for advanced therapy. I did consider those briefly but decided against them.

Duodopa is a pump system that delivers a gel form of the levodopa drug directly into the small intestine. This happens through a stoma in the abdominal wall. The idea is to bypass the stomach digestion processes that can impact the drug. However, having a permanent stoma was not something I would relish.

The other option is Apomorphine, which is the delivery of a dopamine agonist drug through a permanent pump similar to that used by diabetics. That drug, however, can be responsible for sometimes severe side effects such as impulse control disorder.

I had fully and completely considered my options, and I trusted the members of my care team to look after my best interests. I decided that DBS was the way forward for me and I was very much at ease with the decision and the pathway laid out before me.

More workup

Paul was a little more subtle than Raymond, particularly early on. When it came time to do the off-your-meds test, that changed a little. Now, this is a brutal but essential test. I’m examined when I am on (I’ve taken my usual dose of Parkinson’s medications), and when I am totally off (no medications since the previous day).

When I am on, I can do most things. In fact, many people don’t even recognise that there is anything wrong with me. However, being completely off was almost cruel, lifting my arms was akin to moving through treacle. It was at this point that Paul said I was “impressively bad.”

Now, being that bad is not necessarily a negative thing. The fact that I respond so well to the levodopa drug therapy is what ended up making me an ideal candidate for DBS. This is the key thing that Paul is looking for, as the stimulation works best on those who demonstrate a significant response to treatment with medication.

Having been through the testing, examinations and interviews, the team determined that I was indeed an ideal candidate for DBS surgery.

The last step was a quite intense discussion with Paul about expectations. He spelt out in no uncertain terms the fact that DBS is not a cure-all and that it will not eliminate all symptoms. When I am on meds I’m operating at 100 percent capacity, when I’m off I’m operating at zero percent capacity. Paul explained that the DBS would bring the bottom line up to around 75 percent operating capacity, meaning I would never be off again! He also stated that any medication I do take would be the proverbial icing on the cake. I somewhat playfully argued the point here as my ideal ratio of cake to icing is 2:1 rather than the higher ratio he was peddling.

With all parties happy, I went home and waited for about six weeks for a date for the surgery.

Surgery, recovery, and getting turned on

Admission

With the surgery date firmly in place, Katie and I drove the three hours to Sydney. I was admitted to North Shore Private Hospital at 1:00 p.m. on the Monday of the last week in June. Surgery was scheduled for first thing Wednesday, 28 June, which was eight years to the day since I was diagnosed.

To give you an idea of how efficient this private hospital was, between admission at 1:00 p.m. and about 7:00 p.m., I went through the admission process with the nurses, had obs taken, an ECG, a 45-minute MRI, a chest x-ray, spoke with Raymond and Mark (the anaesthetist) and spoke twice with Paul. With all tasks and consultations complete in about six hours, Paul gave me a leave pass for Tuesday so Katie and I could go out somewhere nice for lunch!

The surgery process

I’m not really one for describing things simply for the shock value. I’d prefer to think that this account of my experiences might help others considering the process be a little more at ease with what happens.

DBS surgery happened in two sessions. The first session was the placement of the leads into the brain, which was done while I was under sedation. This part of the procedure took about four hours, commencing at 8:00 a.m. Then the theatre is set up for general surgery, which also coincides with a shift change, so the theatre staff are fresh and ready to go. The second session was implanting the stimulator and lead connection, which was completed under general anaesthetic.

Leads

Up at 5:30 a.m., showered (which in my unmedicated state took ages), and into a surgical gown. A special gown, though, where the two parts of the opening at the back actually overlapped! I then waited an eternity for the orderly to fetch me.

I lay in my bed while it was wheeled from my room, through the hospital to the operating theatre suite, arriving at about 7:45 a.m. In the prep room there were quite a few people, including the anaesthetist and his assistant, and a theatre nurse who came to shave my head. That was no big deal, I’ve been buzz-cutting my hair for 20 years.

The anaesthetist, Mark, gave me a small local anaesthetic in my forearm and inserted a cannula. He has a hugely important job, as he had to sedate me and wake me up multiple times during the procedure.

In order to place the leads in the correct location in the brain, the team must map the pathway for the surgeon to take. Even then, it has been described as like landing a plane in the fog with only a handful of instruments for guidance!

The first step was to fit a stereotactic frame to my head. The frame is able to guide the surgeon to precise locations in X and Y coordinates for entry points into the skull and brain. For the fitting, I moved to a chair and was lightly sedated. The frame was pinned tightly to my skull at four points. I then transferred back to the bed and was wheeled back into the theatre.

To determine the Z coordinate, or how deep into the brain the surgeon must go and the path he must take, a computer is used to make a map from a combination of an MRI (conducted on the Monday) and a CT scan done on the spot in the theatre. This mapping exercise can take a considerable amount of time.

Once the map was finalised, Raymond made a large incision in my scalp and peeled it back to give him access to the two drilling spots. He then drilled the first hole in my skull, about a centimetre in diameter, and a tiny incision was made in the lining of the brain. The lead was inserted, using a microdrive mounted on the frame.

I was brought out of sedation and Paul spoke to me, explaining that it was time for fine placement of the lead. I could hear Raymond behind me saying at a slow, steady pace “ … four, three, two, one, zero, one, two … ” while Paul held my hand in a fist and rolled the wrist back and forth. There was also white noise coming from a set of speakers nearby. What was actually happening was Raymond was feeding the lead into the supposed sweet spot at 0.1 of a millimetre at a time, while Paul checked the rigidity in my wrist, watched my eye rolling and listened to the level of my brain activity on the sound system. Paul asked Raymond to back the lead up a little as my wrist got more rigid. The sweet spot was found when the wrist was no longer rigid.

Once the lead was in the right location, it was secured in place with a small capping device that fitted into the drilled hole. The lead was left to join the connector later on.

Then it was time to move to the other side of the brain. I was still awake and got to experience the drilling of the second hole! Now, the average person might balk at the idea of going through that sort of thing, but I am very pleased I got to experience the whole process. There are no pain receptors in the skull or the brain so I didn’t feel anything, however, I certainly heard the whole thing!!! Imagine you have your ear pressed against a brick wall and someone is trying to put a hole in the wall next to you, using a massive hammer drill and a blunt masonry bit. The noise was absolutely astonishing.

Water was used as a coolant for the drilling and I could feel it run down my head and neck. Apparently, my skull was a centimetre thick, which made the drilling hard going. Once through, the lead was placed into the brain, and secured in the locking cap, adopting the same methods as used on the first side.

Below is a photo taken by Paul, once both leads were set. In the reflection on the right, you can see Raymond’s gloved hands as he works away at my skull. There is a second stereotactic frame on the bench on the left. And yes, I am awake and throwing the horns!

Now, this is where the process got a bit weird. Having completed the delicate task of lead placement, it was time for Raymond to close my incision and staple me up. No stitches, just 23 staples holding the scalp together, and all covered with a narrow strip of heavy-duty bandage. While that was happening a Spotify playlist was switched on and began pumping through the speakers. It seemed to be party time in the theatre and there was much banter. When I asked if the patient who was still awake got the right to veto the song choices, a voice from somewhere in the room said no, and said it in a jocular tone that suggested that I possibly should not have asked. However, they did cede to hear my request, which was promptly ignored. Nathan, the radiographer and the person responsible for the voice that said no, said he would sort out a song for Raymond. The song that came on next was Smooth Operator by Sade!

Fully stapled and bandaged, it was time for the frame to come off. Once again, I remained awake and experienced the unusual sound of the pins being unscrewed from my skull. I likened it to removing wheel nuts that have been on a car too long and too tight. You know, that horrible metal-on-metal squeaky sound. Again, I did not feel a thing, but the sound was incredible!

Half time

With the first half done and dusted, I spent 40 minutes in the recovery ward, waiting for the theatre to be reset for general surgery and the second half action. There was also a shift change meaning fresh theatre staff came on board for the afternoon.

Even though I had been nil-by-mouth for 14 hours, I had been on a fluid drip, so my back teeth were floating. Raymond said I would get an opportunity to have a wee in the break — I promptly put 650 millilitres into a bottle — and then relax while I waited.

Implant and connection

And so on to the second half. With the leads in place deep in my brain and locked into place in my skull, it was time for them to be connected to the stimulator/battery unit.

Mark approached my side and said “Right, you won’t remember any of this, see you later!”, and put me under. The next thing I knew I was waking in recovery to a few people rearranging tubes and fussing about, and Mark said “Welcome back!”

Four hours had disappeared. During that time a couple of key things happened. An incision was made just behind and above my right ear. In that space under my skin, the two leads were connected to another cable. Raymond then created a channel under my skin down the side of my neck to the collarbone. Through this new channel, he inserted the connector cable. It feels just like another blood vessel from the outside. He then made a small incision in my chest, inserted the stimulator and attached it to the chest wall just under the collarbone (and not under my massive pec!). Raymond then connected everything up, tested the system and closed me up. His handiwork with sutures and staples is second to none, and he has one of the lowest infection rates in the world.

There was one small task before we were finished. A quick trip to Radiology for a three-minute CT scan to double-check that everything was in the right place! Then it was off to the Intensive Care Unit for the night!

That was it, at about 4:30 p.m., the day of surgery was over. Done. Complete.

Getting turned on

My wife Katie and her friend Mel came into the ICU shortly after I did. It was a long day of waiting for Katie so Mel decided to keep her company which was very thoughtful. They proceeded to feed me sandwiches and apple juice for which I was extremely grateful.

I wanted a machine that goes “BING!” and the most expensive machine in the hospital in case the administrator came! (something for the MP tragics … )

Then Paul came to visit. He had some bits of tech with him, which turned out to be my DBS remote control and the tablet he uses with the requisite software to program my stimulator, which uploads through the remote control. (More detail on the tech is below).

Paul programmed the initial settings into the software and uploaded them. A slight tingling sensation swept over me. And just like that, I was on! I have not been off since.

I spent the night in ICU but found it very difficult to sleep. Apart from the constant nursing attention, I wanted to be awake — I had survived brain surgery and came through unscathed, unchanged. And my new system was on and working. I wanted to tell everyone. I was excited, relieved, and very emotional.

I was up and on my feet first thing in the morning. The physiotherapist turned up early too, with a large walking frame on wheels for me to use. I guess they must deal with older, less mobile people. I certainly did not require assistance, and I subsequently led her around the ICU for several laps before she stopped me and said I was good to go for a return to the ward.

Tuning

Paul visited a couple of times a day for the next seven days, tweaking the coarse tuning of the system. It was absolutely incredible. I could walk normally and use my hands and arms, and the expression returned to my face. Coinciding with the turning on of the system, I was able to reduce my drug dosage. I halved the dose of the main drug, halved the dose of the secondary drug, and dropped two drugs altogether!!

Fine tuning of the system continues and minor tweaks may happen every now and then for perhaps six months.

Recovery

My wounds were given ten days to heal. At that point the bandages came off and a surgical staple remover was used to remove the staples.

Just seven staples closed the wound on the side of my head.

The main wound across the top of my head was closed with 23 staples.

Staples were removed on day nine. The nurse removed every second staple on the first pass from left to right, then removed the remainder on the second pass from right to left. The nurse explained that it was done this way because the wound can reopen if the staples are removed in order in one direction. I had healed very well so there was little chance of that occurring!

Three weeks after surgery and the scar looks good.

Since I was discharged from the hospital, one of the most difficult things I have had to deal with is that I am not allowed to drive for three months because I have had brain surgery. That hasn’t stopped me from driving from the back seat though!

The tech

Below is an overview of the system I had installed in my body.

a: the leads that were implanted in my brain

b: the connector ends of the leads

c: the two-into-one cable connector

d: the stimulator/battery unit

e: the burr hole cover

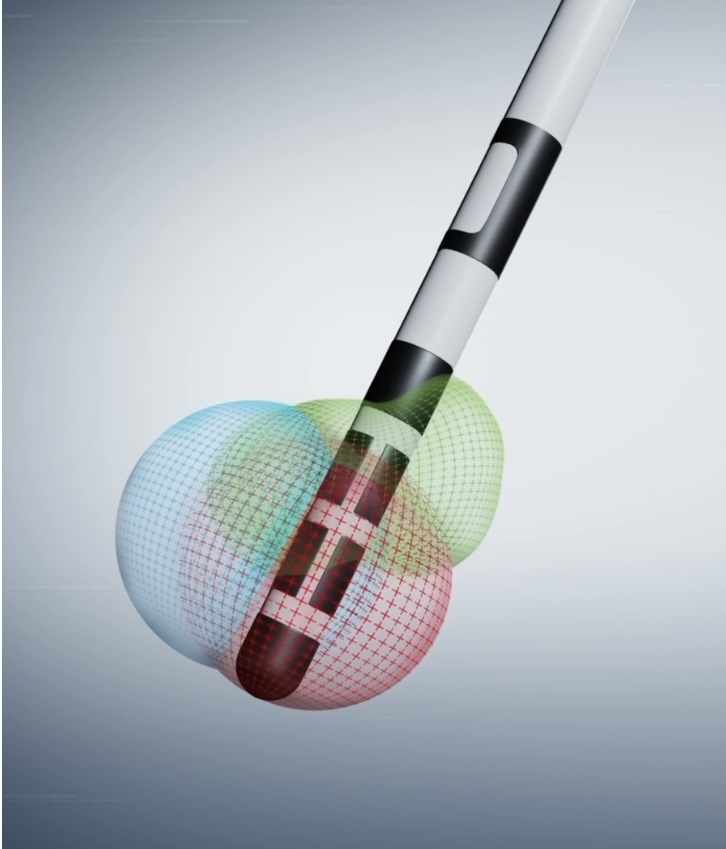

Below is a graphical representation of the lead that was put into each side of my brain. The lead can emit signals from multiple locations, in different directions, at different frequencies and power levels. The DBS team has used multiple generations of directional leads. Other leads simply direct the signal omnidirectionally, perhaps like turning on a torch in the dark.

Below is a pic of the stimulator/battery unit, which is approximately 60 millimetres high and 11 millimetres thick.

The photo below is of Paul’s tablet with the stimulator program in operation. There are actually eights pieces of metal that transmit signals, a solid ring (top), two rings that are split into three pieces each, and the cap (bottom). I’m only currently only using the top four pieces, shown in red.

Below, an image of my remote control (no, you can’t have a go!), and an image of the charger unit (that normally sits on its own charging cradle).

The photo below shows me sitting at home charging the device in my chest. The charger unit sits in the left side of the mesh collar and inductively charges the device. There is a metal counterweight in the other side of the collar. Charging takes just 30 minutes a week.

Horns

I certainly do now have a couple of small lumps on the top of my head. These were created by the attachment of the capping device (burr hole cover) in each drill hole to secure the placement of the inserted leads. I affectionately call these lumps my horns, and I tell people I grind the horns down with an angle grinder, as Hellboy does! It was so hard to take a photo of something that looks and feels so prominent yet doesn’t really look that enormous.

The horns, the baseball seam-shaped scar, the scar and lump behind my ear, and the scar on my chest are all part of the experience and absolutely necessary. They are now integral parts of me and are badges of honour. As power pop genius Chris Lund once sang:

The rumours of my demise

have been greatly exaggerated

I wear my scars with pride

They’re the price of an education

Thank you for reading. Please get in touch if you have any questions or require any further information.

Anthony Overs

Canberra, Australia.

Absolutely amazing – fascinating stuff Anthony! Sandra

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Anthony, Wh

LikeLike

Was there more to this, Bill?

LikeLike

Hi Anthony,

Having attended a Beginners session for birdwatchers at the ANBG with you and a game of baseball between the Canberra Cavalry versus Adelaide last Friday night as your guest, I have seen the positive effects that your surgery. Also you drove to my house and delivered binoculars and field guides. Your recount of the pre-op, operation and post-op result is extraordinary. I feel privileged that you have shared this story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful story Anthony and very inspiring too. You say you don’t feel articulate but your blog shows the contrary – you are very articulate! All the best to you and the family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing report! Wonderful to hear that the procedure has been so successful for you, Anthony. Sounds like a huge improvement in quality of life! Thanks for sharing, and all the best,

Yvonne

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to hear your experience. The positive benefit gives hope for me in my early stages, Bruce Stevens

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bruce. Happy to catch up for a chat sometime

LikeLike

Wow, absolutely incredible. I’m so thankful for the happy ending to a fascinating story. Super happy for you Anthony and grateful to have you as a friend!

LikeLiked by 1 person